June 06 2025

The Dark Side of Solar

Solar panels are symbols of the clean-energy revolution. Yet behind their gleaming promise lies a looming environmental headache: solar waste. As early generations of panels reach the end of their 25-30 year lifespan, a torrent of discarded silicon, glass and heavy metals is set to arrive. Recycling technologies exist, but facilities are scarce. Unless addressed, the world could be trading one environmental problem for another.

A gathering storm

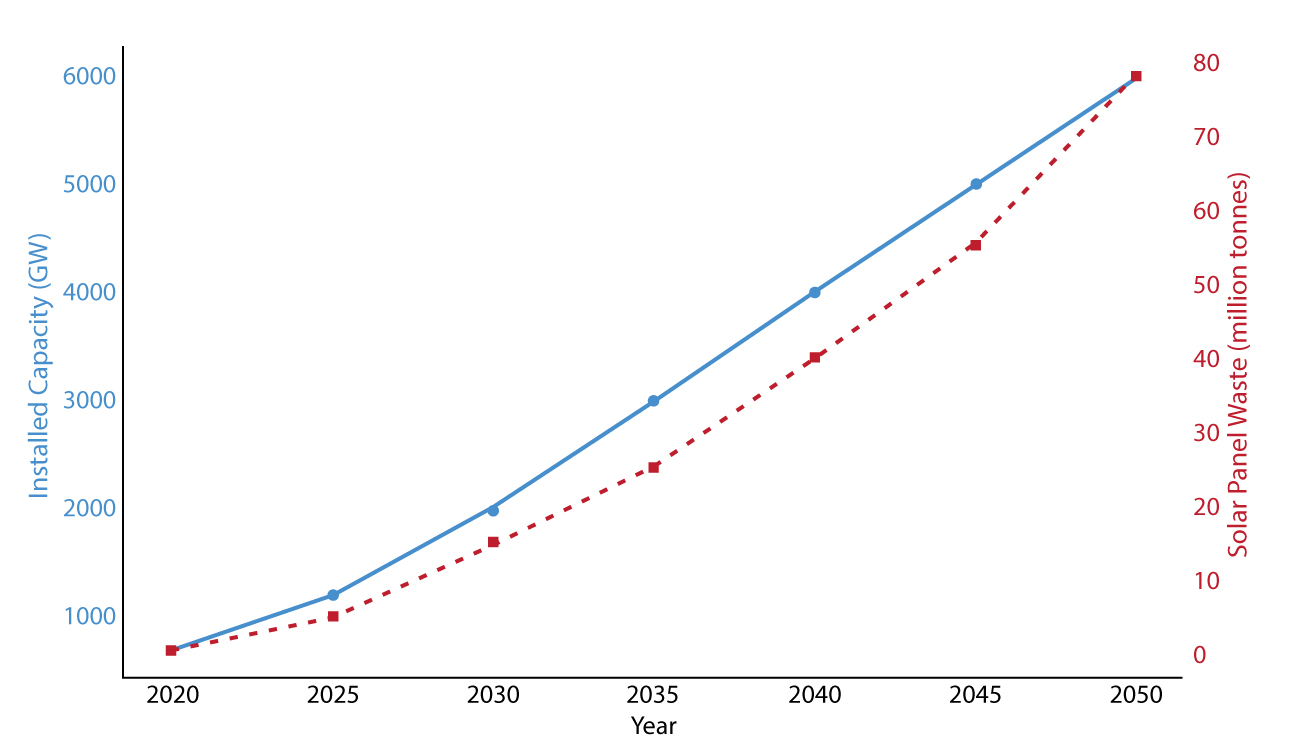

By 2050, the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) estimates that solar waste could total 78 million tonnes globally—equivalent to nearly four times the annual volume of plastic packaging currently produced. For now, the problem is manageable. Most of today’s panels are still generating electricity. But the first big wave of early-deployed modules, particularly in Europe, Japan and the United States, is now reaching retirement.

“People see the shiny new panels on rooftops and assume they’re entirely green,” says Dr. Anika Schultz, a researcher at the Fraunhofer Institute in Germany. “But every solar array is also a future waste stream.”

Projected global solar panel waste to 2050 (in million tonnes), alongside projected installed capacity growth

Source: ARIA, Technical Papers

Where the problem bites hardest

The most acute challenges are surfacing in the European Union and Japan, which rolled out large-scale solar programmes in the early 2000s. Japan expects over 800,000 tonnes of solar waste annually by 2040. In Europe, the WEEE Directive (Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment) already obliges producers to collect and recycle panels, but actual recovery rates remain low. America, meanwhile, has no federal mandate—only a patchwork of state-level initiatives, leaving many panels destined for landfill.

Emerging markets such as India and China face an even starker prospect. China alone is home to one-third of the world’s installed solar capacity. Its panels are newer, but when they begin to retire in the 2030s, the scale of waste will dwarf anything seen in the West.

“We are staring at a cliff edge in the 2030s,” warns Michael Thompson, an analyst at Wood Mackenzie. “And right now, the parachute isn’t ready.”

Where do old panels go?

When not recycled, solar panels typically end up in landfills or are incinerated, with obvious environmental downsides. Panels contain valuable materials—silver, silicon, aluminium, copper—but also toxic components such as lead and cadmium. Landfilling risks leaching heavy metals into soil and groundwater, while incineration squanders recoverable resources.

Collection systems remain patchy. In the EU, producers fund collection under WEEE. In the United States, homeowners are often left to arrange costly removals. In poorer countries, panels may simply pile up in informal waste yards, stripped for scrap.

Attempts at a cure

Several countries are beginning to confront the problem. The EU is furthest along, with France hosting Europe’s first dedicated solar panel recycling plant, operated by Veolia, capable of processing 4,000 tonnes annually. Japan has launched a government-backed project to subsidise recycling firms. In America, Washington State requires manufacturers to finance recycling, while California is piloting take-back schemes.

Private firms are also stirring. ROSINTAL in Germany is developing high-efficiency thermal treatment to recover silicon wafers. First Solar, a US manufacturer, runs its own in-house recycling programme, reclaiming 90% of glass and semiconductor material. Startups in Australia and India are experimenting with hydrometallurgical processes to recover silver and rare elements.

“The technology is not the bottleneck,” argues Sophie Liang, CEO of PV Cycle Asia. “It’s the economics. Virgin materials are still cheaper than recycled ones.”

Rules in the making

Regulators are beginning to catch up. Brussels is debating stricter recycling quotas for solar under the forthcoming revision of its waste legislation. In America, the Environmental Protection Agency is considering whether panels should be classified as hazardous waste nationwide. India has signalled it will introduce Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) rules for solar.

But the incentives are still weak. Without mandates or subsidies, recycling often costs more than landfilling. Policymakers face a choice: either absorb those costs through regulation, or risk an environmental backlash that undermines solar’s green credentials.

The road forward

Fixing the problem will likely require a three-pronged approach: stronger regulation, technological innovation, and market creation for recovered materials. If recycled silver or silicon can be made cheaper than mined alternatives, the industry could self-correct. Scaling plants to industrial size would also slash unit costs.

For now, however, solar recycling remains a niche. “It feels like the early days of battery recycling,” says Dr. Schultz. “Nobody cared until the waste started piling up. Then it became urgent.”

The global solar industry has built itself a reputation as a clean-energy champion. Unless recycling infrastructure catches up, it risks facing an uncomfortable irony: an energy transition undermined by its own waste.