May 22 2025

Tariffs and Turmoil: Commodities in the Firing Line

Tariffs, once dismissed as a relic of mercantilism, are again shaping the global economy. As of May 2025, the new wave of trade barriers announced by Washington—chiefly aimed at China but rippling far wider—has sent fresh tremors through commodity markets. The logic in Washington is simple: shield American industry from predatory imports, claw back manufacturing jobs, and assert control over supply chains deemed strategic. The reality is proving far messier, with markets for metals, energy, and agricultural goods lurching as traders scramble to adjust.

Early winners, sudden losers

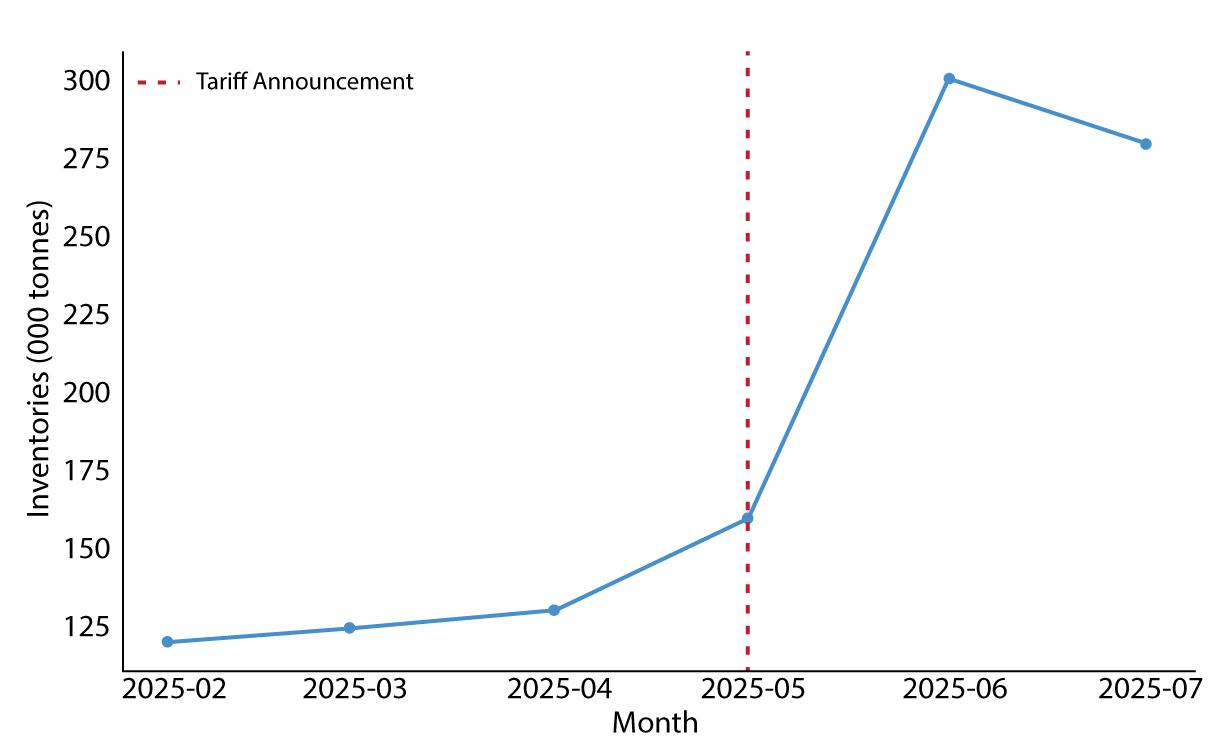

The sharpest tremors have been felt in metals markets. Copper, aluminium, and nickel, vital to green-energy supply chains, have seen pronounced volatility as traders seek to front-run tariffs. On the COMEX exchange in New York, inventories of aluminium suddenly swelled in April as shipments were rushed into warehouses before tariffs took effect. That stockpiling caused a temporary glut—spot prices softened while futures premia widened, reflecting uncertainty about longer-term availability.

Chart: Frontrunning : COMEX aluminium inventories spike

Source: ARIA, Various, Bloomberg

Meanwhile, in steel, America’s perennial target, tariffs have emboldened domestic producers but raised costs for manufacturers downstream. The result: American steel prices are again trading at a significant premium to global benchmarks, rekindling complaints from carmakers and construction firms.

Testimonial

"We had clients moving cargoes weeks ahead of schedule to avoid the tariff wall," says a metals logistics manager in Rotterdam. "The short-term distortions are huge—some ports look like parking lots for aluminium and copper."

The Sino-American battle lines

The political backdrop is familiar. Washington accuses Beijing of flooding global markets with subsidised green tech—solar panels, batteries, and electric vehicles in particular—at prices that undercut Western producers. China, in turn, sees America’s tariffs as naked protectionism, undermining global trade rules. The confrontation is not limited to finished goods: rare earth elements and critical minerals have moved centre-stage.

China controls around 70% of global rare-earth output and an even larger share of refining capacity. These obscure but indispensable elements power magnets in EV motors, wind turbines, and missile systems. American tariffs on downstream Chinese products risk provoking Beijing into weaponising its rare-earth dominance, as it briefly threatened in 2019. Already, rumours swirl that export licences for dysprosium and terbium (two particularly critical rare earths) could be tightened.

Testimonial

"Rare earths are China’s ace card. If they restrict exports, it would ripple through everything from iPhones to fighter jets," warns an executive at a Japanese trading house.

Agricultural flashpoints

Soybeans, America’s largest farm export to China, once bore the brunt of retaliatory tariffs in the last trade war. Farmers in the Midwest now watch nervously. Although China has diversified imports to Brazil and Argentina, it still buys millions of tonnes from the U.S. A renewed Chinese boycott would squeeze American farmers just as they face higher input costs from fertiliser and fuel.

Energy markets, by contrast, have been less rattled. China has diversified its oil and LNG suppliers to the Middle East and Russia, while America has plenty of buyers for its shale-driven exports. Still, any escalation risks reordering flows, pushing shipping costs higher and adding friction to trade.

Trump’s wager

Donald Trump, seeking re-election on a hawkish trade platform, argues that tariffs are a blunt but necessary tool to restore American competitiveness. By penalising imports, the administration hopes to reshore factories, protect jobs, and accelerate domestic investment in green supply chains. Proponents argue that tariffs are a lever to pry open negotiations with Beijing on subsidies and market access.

The economics, however, are contested. While U.S. producers of aluminium or solar panels may benefit, downstream users—from carmakers to construction firms—pay higher prices. The IMF estimates that every 10% tariff on intermediate goods can shave 0.3% off GDP growth if retaliation follows. For a world economy already flirting with stagflation, the risks are evident.

China’s countermoves

China’s options are varied. It could respond in kind with tariffs on U.S. agricultural and industrial exports. More subtly, it could delay approvals for American firms operating in China, or selectively restrict exports of critical minerals, including gallium and germanium—both essential for semiconductors. Such asymmetric measures would bite most in industries where substitution is difficult.

At stake is more than bilateral trade. Tariff salvos disrupt global supply chains, rerouting flows of metals, energy, and food. That undermines the fungibility on which commodity markets thrive. What should be a global pool of resources risks becoming balkanised, raising costs for all.

A fragile equilibrium

The longer tariffs remain, the more they reshape flows permanently. Brazilian soybeans may replace American ones; Kazakh rare earths may attract investment long delayed; and COMEX warehouses may swell again with pre-emptive stockpiles of metals. In the meantime, traders thrive on volatility, but industrial users are left footing the bill.

Tariffs may please political crowds, but for commodity markets they are less a remedy and more an irritant—a reminder that economic nationalism, once unleashed, rarely comes without a price.